Image courtesy of ABAJournal.com

For many years, surrogacy laws around the world have been in flux. Currently, the Canadian Parliament is considering a bill that would repeal the current legal prohibitions against paying for a surrogate. In the UK, the Law Commission of England and Wales and the Scottish Law Commission have announced they will review various laws that regulate surrogacy as part of an effort to speed up the granting of parental orders and deter the exploitation of birth mothers abroad.

Surrogacy remains a hotly contested and complex issue, and there is no consensus on how to regulate it around the world. Can any one legislative approach tackle the many ethical, legal, moral, cultural, religious, etc. tensions that arise in this context?

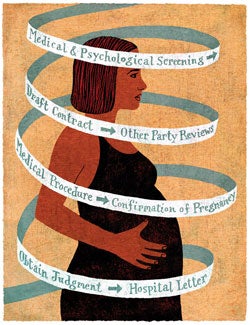

A surrogacy arrangement is entered into by the surrogate (who carries a child to term on behalf of the intended parents/s) and the intended parent/s (who raise/s the child after the surrogate has given birth). There are various types of surrogacy, including traditional or partial (the surrogate’s genetic material is used to conceive the child, in addition to that of the intended parent or donor ), gestational (all of the genetic material involved originates from the intended parent/s and/or donor/s), commercial (a surrogate is paid a fee above and beyond reimbursement for expenses for the service) and altruistic (a surrogate volunteers to perform the service and only receives reimbursement for expenses).

Surrogacy laws around the country take many forms. In some countries, it is tolerated (e.g. Luxembourg and Poland) or expressly legalized (e.g. India, Mexico, Russia and Thailand). In others, it is completely (e.g. France, Spain and Turkey) or partially (e.g. Australia and Canada) banned. Within some countries, such as the U.S., individual states have adopted different approaches to regulating surrogacy.

Regulating surrogacy at the national level is a difficult task for numerous reasons. For example, surrogacy legislation seeks to simultaneously protect the interests and rights of various parties (i.e. the intended child, the intended parent/s, the surrogate, etc.). When countries regulate the practice, moreover, it can be difficult to do so in a manner that is not only consistent with local moral values and religious traditions, but also internationally-established principles of ethics and human rights.

Unfortunately, the lack of consensus among countries, as well as states within countries, about how to regulate surrogacy can have troubling implications at the global level. International surrogacy arrangements are common, as intended parents in countries with restrictive surrogacy laws are increasingly finding ways to use surrogacy services in countries with more liberal laws. But laws around parentage and citizenship vary from country to country, which can result in the birth of stateless children. For example, a child could be neither a citizen of the intended parents’ home country, because its laws prohibit surrogacy, nor a citizen in the surrogate’s country, because parentage in that country is genetically determined and the surrogate mother is not genetically related to the child.

Differences between countries’ laws, particularly in the context of surrogacy, may always exist. But there is an urgent need to prevent or mitigate the negative consequences that can result from such differences.