I recently read an article in Forbes that asked, “Are [foodborne] outbreaks actually increasing, or are we just more aware of them?”

I work in food safety. I often feel panicked before I feed my children. But I thought that might just be a hazard of working in this field.

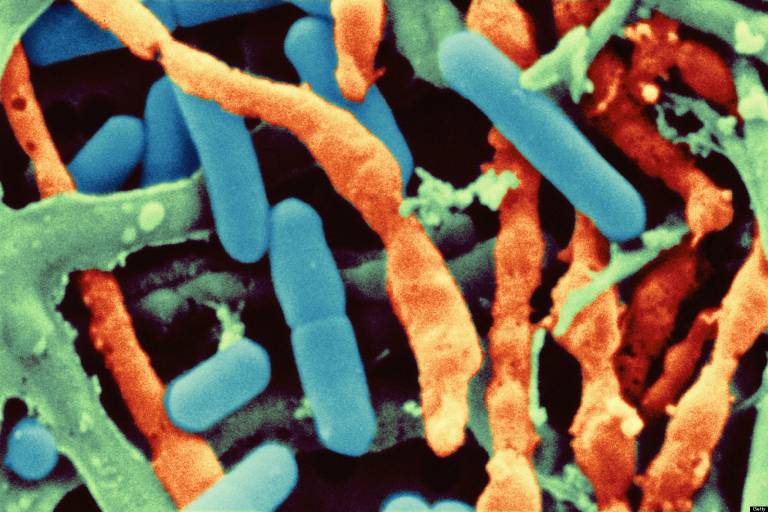

So, are foodborne outbreaks actually increasing? That’s not really clear. Advances in diagnostic technology, including the ability to sequence the genome of a particular pathogen, and epidemiological improvements in reporting have greatly contributed to public recording of outbreaks. Couple that with the nationalized reality of the food supply in the United States. As the reach of any single distributor continues to expand, the scope, scale and impact of pathogens in our food supply is felt more broadly.

While pregnant I was told no deli meats, sushi or unpasteurized cheese. The fear was listeria monocytogenes, a bacterium known to cause miscarriage in pregnant women and severe illness or even death in the young, old and immunocompromised. Avoiding the riskier foods was easy. I did however eat lots of hummus, spinach and ice cream, three of the sixteen foods recalled just in the last two months because of listeria contamination.

It feels like each day there is more salmonella in peanut butter, campylobacter in poultry and shigella in food generally.

At a recent food safety conference, I sat next to a father whose four-year-old son died after contracting E.coli from another child in the same daycare facility who ate one of the infamous Jack-in-the-Box hamburgers in 1993.

And still, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that each year roughly 1 in 6 Americans (or 48 million people) get sick, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die of foodborne diseases. This means that in the more than twenty years since that deadly e.coli outbreak, we can assume approximately 66,000 people have died from the adulterated food products.*

For an excellent summary of the status of food safety in America, see this 11-minute NYT piece.

The real question is what improvements are being made when it comes to prevention? Preventing the presence of dangerous pathogens in food was the hallmark of FDA’s 2010 Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). As FDA works diligently to implement FSMA’s rules, they are also looking to the private sector and other non-governmental institutions to support their mandate.

Last fall, FDA and the CDC announced the 2014 Food Safety Challenge created to spur innovation in academia and the private sector in the field of pathogen detection. Specifically, the first challenge promised an award of $500,000 to the inventor of technology to detect salmonella in fresh produce. Yesterday, FDA announced five finalists. While the scientific merit of these projects far exceeds my legal background, the significance is transparent. The only way to be sure that food borne illness is on the decline is to stop it before it starts.

*Disclaimer: I did not check whether CDC estimated deaths to be 3,000 people per year for each year since 1993. But for argument’s sake, we can safely assume the number is significant.

Latest

Mantener la prohibición de la exhibición indirecta de productos de tabaco salva vidas

Ariadna Tovar Ramírez Fernanda Rodríguez-Pliego