Most infectious disease epidemics target the body, and thus epidemic response focuses on preventing the spread of infection and attempting to heal those who have become ill. However, even where pathogenesis disregards the brain, an epidemic can still sicken the mind. A silent epidemic of mental illness often accompanies outbreaks of infectious disease.

Here I hope to highlight a few of the myriad impacts epidemic diseases have on mental health. I contend that epidemic responses that also respond to the mental health of the affected population will not only improve psychological wellbeing, but will also aid in fighting the epidemic, since poor mental health can impede efforts to fight the disease.

Fear and isolation of the sick and quarantined

The patients arrive, at first fearful of the people in spacesuits whose faces they cannot see. They wait for test results, for the next medical rounds, for symptoms to appear or retreat. They watch for who recovers to sit in the courtyard shade and who does not. They pray.

– New York Times reporter, Daniel Berehulak, describing the scene at an Ebola treatment center in Liberia

Those who are sick and those who are quarantined – particularly in epidemics with high mortality rates – suffer tremendous mental strain. It is hard to imagine avoiding psychological distress in the face of being infected or at risk for a highly lethal disease such as Ebola or Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

In fact, many studies have documented connections between serious illness and a range of mental illness. To provide just a few examples: cancer has been associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); SARS with PTSD, anxiety, and depression; and HIV with PTSD.

Finally, those who are quarantined, even if they never become infected, can suffer profound mental health issues that last long past the end of their quarantine. A 2006 study found that 29% of those quarantined during the SARS outbreak showed signs of PTSD and 31% demonstrated signs of depression. Moreover, at least in the case of PTSD, the longer someone was quarantined, the more likely they were to show signs of the illness.

Breakdown of social support structures

Fear began to break down the community of the city. Trust broke down. Signs began to surface of not just edginess but anger, not just finger-pointing or protecting one’s own interests but active selfishness in the face of general calamity.

– John M. Barry, The Great Influenza (2005), p. 329

Medical professionals have long understood the importance of strong social networks to mental health. Epidemics can abruptly tear down social support structures when they are needed the most, leaving individuals feeling isolated and vulnerable.

In the face of an epidemic many of the places where people gain social support, such as churches, schools, and workplaces, may be shut in an attempt to stop the spread of disease. And even smaller social interactions, such as visiting the home of a friend, may cease for fear of contracting the disease.

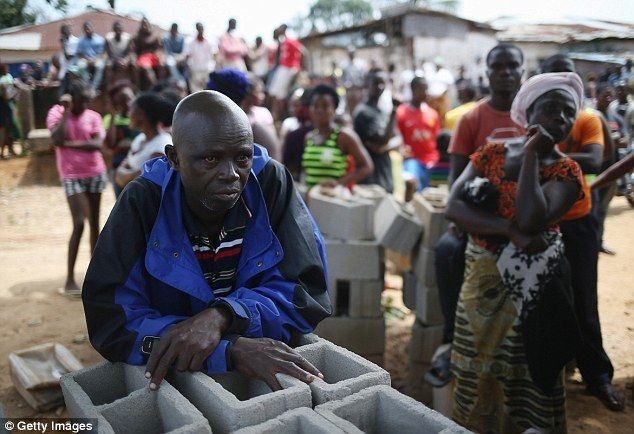

The breakdown of social support can even extend to the most intimate and arguably most important tie – family: “In some communities, the fear surrounding Ebola is becoming stronger than family ties,” according to one UNICEF official. In a particularly powerful and heartbreaking piece, New York Times journalist Norimitsu Onishi documents how the death and mistrust surrounding Ebola tore one family apart. Mr. Onishi fears that Ebola’s wide-reaching impact on West Africa’s social fabric will outlive the disease.

On a continent with many weak states, the extended family is Africa’s most important institution by far. That is especially true in the nations ravaged by the disease — Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea — three of Africa’s poorest and most fragile countries. Ebola’s effects on the region, in undermining the very institution that has kept its societies together, could be long-term and far-reaching.

Stigmatization of those with disease

My youngest sister loved to play with other kids in the neighborhood. One day she was playing with Chris, a ten-month-old baby boy, and she was kissing Chris who was laughing. Suddenly Chris’s mum, who was watching them through the window, came running and took Chris out of my sister’s arms, saying: “Don’t ever come back here, I don’t want you to infect my baby with AIDS. Don’t try to kill my baby. We all know that you are dying of AIDS.”

– Claire Gasamagera describing her experience with stigma in Rwanda

Stigmatization is yet another mechanism of social isolation caused by epidemic disease outbreaks—and itself a cause of mental illness. Individuals and communities often turn against each other or against others, resulting in fear, mistrust, and ostracization.

The most obvious targets of stigmatization are those living with the disease. However, whole communities and populations are often the target – Asian Americans during SARS, West Africans during Ebola, Haitians and gay men in the early days of AIDS, to name just a few. This “epidemic within an outbreak” removes social support systems and undermines mental health.

In some cases stigmatization can lead to patients avoiding the healthcare system for fear of being ostracized. This has been a significant problem with AIDS, where people living with HIV or AIDS avoided testing and treatment due to the stigma associated with the disease.

Impact on the health system

An epidemic’s impact on the health system can impede both mental and physical health. This impact works in two directions: (1) health workers’ mental health often suffers as a result of working during epidemics and (2) strained health systems result in less access to mental health services.

Health workers often suffer mental illness as a result of the stress and trauma of working during a disease outbreak. One study of health workers after the SARS outbreak showed nearly one-fifth had developed “significant mental symptoms.” Medical professionals who develop mental illness are likely to be less productive – thus poor mental health can weaken the response to the epidemic itself.

Second, at a moment when mental health services are most desperately needed, epidemic disease may undermine the health system’s ability to provide it. Health professionals, overwhelmed with dealing with the outbreak, often are forced to neglect other medical concerns. And in the case of deadly and easily transmissible infections large numbers of health workers may die, leaving health systems under even greater strain. Patients may also avoid healthcare settings for fear of contracting the disease. Already there is concern about the impact Ebola has had on the fight against AIDS, and routine health services such as vaccination.

Conclusion

Even epidemic diseases that limit their attack to the body can cause a mental health crisis. It is thus imperative that epidemic response and recovery include plans for addressing mental illness.

Fortunately, good roadmaps already exist. A report by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee, formed by the United Nations to better coordinate international response to humanitarian emergencies, provides a good outline. An article from the Journal of the American Medical Association, published earlier this month, highlights the most urgent priorities in dealing with mental health issues that have arisen from the Ebola epidemic – many of which have wider applicability.

Implementing these recommendations in the face of epidemic disease will not be easy. It will require creativity along with a significant commitment of resources and political will, both at the national and international levels. However, the gains to health – both mental and physical – will repay such an investment.