Last April 29 was the first official world day for safety and health at work. The International Labor Organization inspired by its centenary anniversary, attempted, with the establishment of this date, to reaffirm the importance of a healthier workforce as a prerequisite for a brighter future of work and a more sustainable development. It was also the perfect occasion to launch a global report to share not only the story of a 100 years in saving lives and promoting safe and healthy working environments but which also invited international community to the promotion of occupational safety and health through significant changes in technology, demographics, sustainable development including climate change and changes in work organization.

Safety and health at work bring together the expertise and genuine concern of two United Nations Agencies, the ILO and the WHO. Labor rights, health and safety services, and social protection become the ingredients to face the human cost resulting from the vast daily adversity and the economic burden of poor occupational safety and health practices globally, which is estimated at 3.94 percent of global Gross Domestic Product each year. As the ILO had stated, every year 2.78 million people die as a result of occupational accidents or work-related diseases. Additionally, there are some 374 million non-fatal work-related injuries each year, resulting in more than four days of absences from work.

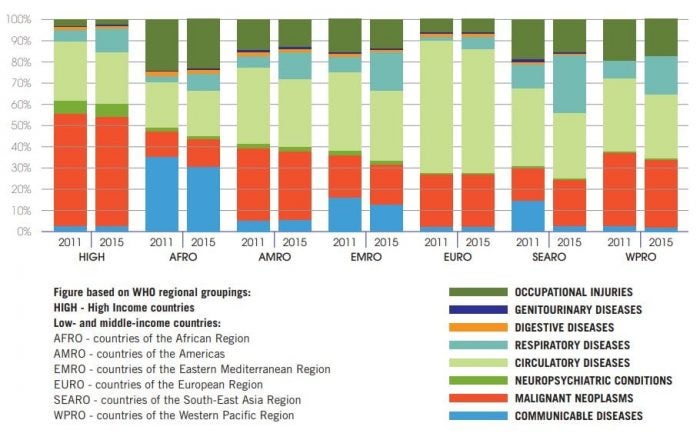

Comparison of fatal work-related mortality by WHO regions between 2011 and 2015

Source: ILO, Safety, and health at the heart of the future of work. 2019

According to WHO and ILO estimates, there are differences in relative contributions of various causes of work-related mortality by region which reflect the multiple and multi-faceted national, social, political, demographic and occupational differences between countries and regions. It also shows, the different capacities to manage health and safety issues in workplaces and various roles of national governments to effectively put in place and enforce health and safety rules.

Even when the importance of improving safety and health at workplaces is increasingly recognized, providing an accurate picture of its global scale remains difficult. To create global awareness of the dimensions and consequences of work-related accidents, injuries, and diseases, and to place the health and safety of all workers on the international agenda, the strategic action of both the WHO and the ILO is required. However, this has not been the first time that joint efforts within the United Nations had existed to prioritize one particular concern. To give a couple of examples, since 1996 UNICEF, and the ILO have been strengthening their cooperation in the global fight against child labor. Peacebuilding and post-conflict recovery had created a long-lasting joint commitment between agencies and programs like UNDP, ILO, IMO, UNHCR, World Bank, among others. Collaborative efforts can result in immediate programs and funds for a particular issue or can result in the constitution of a new specialized entity. We must remember that UNAIDS was born in the nineties as Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS which is a joint venture which brings together the efforts and resources of 11 UN system organizations to unite the world against AIDS.

For this case WHO and ILO differentiate capabilities and strengths are fundamental to stimulate and support practical action at all levels. On one side, the WHO has a long-standing practice working with countries to extend universal health coverage and had developed burden of disease studies that have been essential for the last two decades to obtain consistent and comparative descriptions of the burden of diseases and injuries and the risk factors that cause them. These have become, in turn, an essential input to health decision-making and planning processes. However, it’s the WHO understanding of enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health as one of the most fundamental rights, and its commitment to universal healthcare and a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being for all, that makes its role essential to achieve a reduction in mortality and morbidity caused by work accidents and labor-related diseases.

On the other side, the ILO whose mandate relies in the premises of social justices and decent work counts on a tripartite constitution (involving Governments, Labor Unions and Employers organizations) which facilitates the insertion of any initiative both into the public and the private sector and guarantee bread participation through social dialogue. Also, it´s statistical experience enables the creation of a joint methodology to estimate the health impacts of occupational risks. Moreover, it´s knowledge and practice over comprehensive life-oriented systems materialized in specific departments in social protection and safety and health at work, make it a mandatory partner. Nevertheless, in my perspective, one of the most significant benefits of the ILO presence is its role as the only un agency capable of creating international norms. Safety and health in workplaces result in a bridge that enables both the ILO and WHO to used formal legal instruments mandatory for those countries that had ratified its Conventions and adopted the Recommendations, to influence public policy, local implementation and generate accountability between member countries.

The WHO can capitalize on the existence of international law materialized in more than forty conventions and recommendations explicitly dealing with occupational safety and health, as well as over forty codes of practice, to improve its role in health regulations compliance. Given the nature of the ILO Conventions (international law treaties), countries can ratify, adopt, and implement them into national legislation. Moreover, even though there is no international labor court as such, Conventions can rely on their enforcement on the decisions of domestic courts. Finally, through its supervisory system, the ILO examines the application of standards in member States and points out areas where they could be better applied as a way to bolster its monitoring mandate. These international normative assets can be helpful for the WHO, whose technical expertise is deep but its compliance mechanisms in the international and national legal arena, are not as extensive.