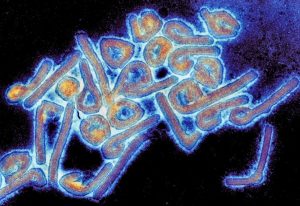

Micrograph of Marburgvirus (credit: The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston)

Last month, the Ugandan Ministry of Health (MOH) declared an outbreak of Marburg Virus Disease (MVD) in Eastern Uganda. To date, three cases have been reported (two confirmed, one probable), and all have died, resulting in a case-fatality rate of 100% for the outbreak. News of the outbreak led many to wonder: what is Marburg?

In a sense, Marburg is Ebola’s sister. More accurately, Marburgvirus is member of Filoviridae, a family of viruses that includes Ebolavirus, meaning they are similar in their structural and genetic makeup. They both cause severe hemorrhagic fever in humans and other non-human primates, and both have very high case-fatality rates. The endemic zones for the two viruses overlap a great deal, as they are both found in Central Africa. Scientists have long suspected that bats are somehow connected with the transmission of Ebolavirus to humans, while with Marburg, the association is known.

Marburgvirus was discovered in 1967, as a result of two simultaneous outbreaks in Germany and in Serbia; the disease is named for a town north of Frankfurt. (Note: the first Ebola outbreak in 1976 was actually two simultaneous outbreaks as well, though much closer together geographically, such that they were determined not be the same outbreak until several years later.) The German and Serbian outbreaks were similar in that they both involved laboratory workers that had become exposed to the virus after handling African green monkeys that had been imported from the same source in Uganda.

Historically, MVD outbreaks have been fewer than those of Ebola – the CDC recognizes twelve, not including the current outbreak. Similar to the current outbreak, MVD outbreaks tend to be small, with respect to the number of fatalities. Twice, however, MVD outbreaks have been large: 128 died in northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo between 1998-2000, less than 100 miles from the Ugandan border; later, in 2004-2005, 227 died during and outbreak in Angola. The majority of outbreaks have taken place in or stemmed from Uganda or neighboring Kenya; the Angola outbreak and a small outbreak originating in Zimbabwe are outliers.

So, should we be fearful of a large-scale outbreak of Marburg, similar to what we saw in 2014-2016 in West Africa? No… but perhaps yes.

Marburg outbreaks, like Ebola, tend to emerge suddenly. But the mysterious nature of Ebola—its unclear linkage with its not-yet-fully-understood viral reservoir—is a characteristic not shared with its sister, Marburg. As such, health authorities within the Marburg endemic zone, such as in Uganda and Kenya, are able to respond to outbreaks somewhat effectively, using contact tracing to determine the source of the disease. In most cases tends to be a cave where bats roost, where a hiker has unwittingly wandered in and exposed themselves, or where bats have been collected for laboratory use. The regional expertise, public health infrastructure, and the developed understanding of Marburg make outbreaks within its endemic zone more capably dealt with.

However, as we hopefully learned from the West African Ebola outbreak, we should know that, like Ebola, Marburg may emerge outside of its endemic zone, and in places with weak public health infrastructures, microscopic doctor-to-patient ratios, and inexperience with diagnosing the disease. Marburg may be less temperamental or volatile than her sister, but that doesn’t mean we should treat her with kid gloves. She deserves as much attention and respect as her sister.