Last week, the Global Fund met its replenishment target of $14B. The news was greeted mostly with sighs of relief, especially because it was a near thing. The Global Fund is the largest star in the global health firmament, channeling more money than any other multilateral actor.* It has leveraged this funding to impressive ends. Since 2003, the Global Fund has disbursed more than $43 billion in more than 100 countries, saving (by their estimates) 32 million lives. So the fact that the Global Fund met its replenishment target, despite the current isolationist environment and with two other major replenishments coming up (Gavi, GPEI) this year, is unquestionably a good thing. But beneath the relief, there is a simmering debate over scope of the Global Fund’s mandate and the balance of resources among global health institutions more broadly. In the days after the replenishment conference, I took part in two conversations which highlight the differing views within the global health community.

On the one hand, some people are arguing that the Global Fund’s mandate should be expanded. (Samy Ahmar’s op-ed makes this case eloquently.) Exactly as its name suggests, the Global Fund was created as financing institution to fight three diseases: HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria. (It has since incorporated a sub-focus on health systems strengthening.) Going by the adage that one’s budget is the truest indicator of one’s priorities, the fact that the Global Fund receives more money than any other multilateral institution creates the impression that fighting those three diseases is the highest priority in global health. Many experts argue that it shouldn’t be. As Ahmar puts it, “[a] great many of us believe this effort now needs rebalancing, at a time of rapidly changing global health needs: the rise of noncommunicable diseases, the increasing frequency of major outbreaks, the risks of a global pandemic, climate change, antimicrobial resistance and the resurgence of old and newer infectious diseases. None of these major challenges can be met without much stronger, better funded, and more resilient health systems for all… The time has come to broaden its scope and mandate beyond HIV, malaria, and TB and make health system strengthening not a means to an end, but the end that justifies all means.”

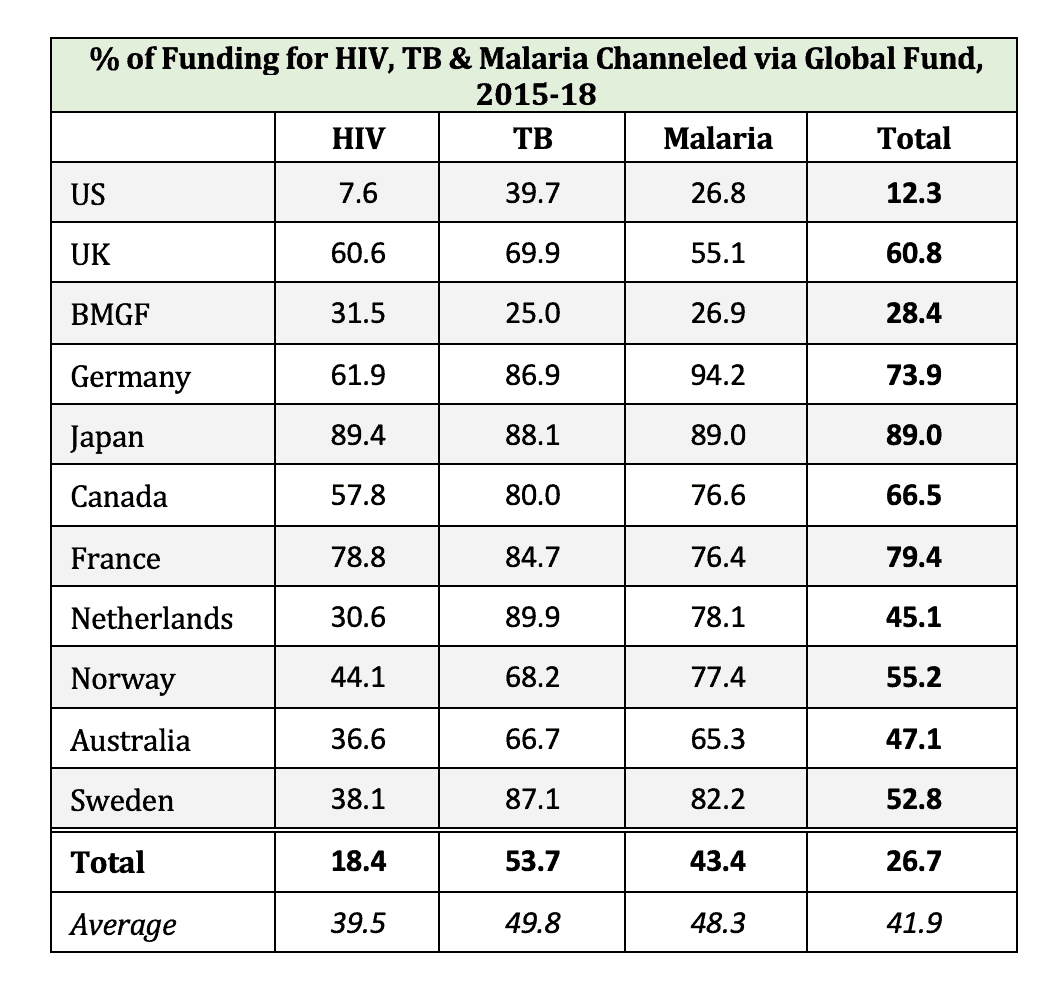

On the other hand, Matt Kavanagh pointed out to me that, excellent though $14B over 3 years might be, it’s not sufficient to meet the targets which the international community has set around ending HIV, TB, and malaria. WHO estimates the funding gap at $14.5B.** So, crudely, the Global Fund money gets us halfway there. The problem arises if donors assume that fully funding the Global Fund equates to fully funding the fight against HIV, TB, and malaria and put away their checkbooks. The evidence on whether they do so is mixed. Using IHME data, I calculated that the amount of money that the top 10 donor countries, plus the sui generis Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, have allocated towards HIV, TB, and malaria since 2015 and the percentage of that money that they channeled through the Global Fund. As the table below shows, the donors in the middle of the top ten (Germany, Japan, Canada, and France) direct more than two-third of their funding through the Global Fund. But for the donors towards the bottom of the list, that number is around half. And for the US and BMGF, Global Fund contributions are only a small percentage of the overall money spent.

In short, some people are saying that since the Global Fund gets so much money, it needs to do a wider range of stuff. Other people are saying that the Global Fund doesn’t get enough money to fully achieve its core mandate. So where does that leave us? Coming off a four-year project on how to make global health governance institutions work better, here are my take-aways:

- Don’t mess with success

The Global Fund is good at what it does. Let it keep doing that. Reams of social science research show that mission creep is a good way to make effective organizations less effective.

- Mandates and money follow priorities, not the other way around

There’s no question that building health systems and achieving universal healthcare is the most effective, efficient, and just way forward in global health. If donors aren’t prioritizing those strategies, our task is to convince them to do so.

In creating partnerships like the Global Fund, donors chose to build the institutions they want to fund, rather than simply funding whatever institutions were already there. Thus, we can’t simply assume that if the Global Fund didn’t exist, donors would have directed that money towards other global health other organizations and priorities. Whether they would have or not is a complicated counterfactual question, requiring in-depth empirical research to answer. (To my knowledge, that work hasn’t been done yet.) What we do know is that donors created the Global Fund, and gave it a narrow mandate, in large part because they did not want to direct their money towards other organizations and other priorities. By extension, we shouldn’t assume that if the Global Fund does shift its focus, donors will simply go along and continue to sign checks with the same enthusiasm.

- We don’t need the Global Fund to be a jack of all trades

Lest we forget, we already have a global health institution with an expansive mandate—one which is leading the charge on universal healthcare/health systems strengthening, even as it struggles for funding. Love WHO or hate it, I think we call all agree that we don’t need another one.

*IHME Global Health Financing data shows that the Global Fund channels more money than other global health institution—though not more than WHO and Gavi put together (as has been reported) except in 2017. (Yearly data from 2017 and earlier is here; 2018 data is here).

**WHO’s calculations factor in the Global Fund’s budget in past years, which will be roughly similar over the next three years.