DIALOGUES ON BEING HUMAN: Intersections of Art, Health and Dignity with artist Jesse Krimes in dialogue with Marc Howard of the Prison and Justice Initiative moderated by Alicia Ely Yamin, Director of the Health and Human Rights Initiative.

Jesse Krimes with his work Apokaluptein 1638067 (The title combines the Greek root of the word “apocalypse,” or “redemption,” and Krimes’ Federal Bureau of Prisons ID number) a 15 foot high x 40 foot wide, 39-panel mural on prison bed sheets, created over 3 years, smuggled out, and pieced together when he was released.

Artist Jesse Krimes conveys the dehumanizing experience of incarceration through his compelling body of artwork clandestinely produced over 6 years on the inside while doing time for a non-violent drug offense. Saying that he only survived his odyssey through the criminal justice system by producing art every day, the work embodies themes of alienation, purification, redemption, social stratification and power. Awaiting sentencing in a 23 hour maximum security lock down for one year, he created 292 separate portraits, mostly of offenders, on slivers of prison-issued bars of soap. Then while serving a 70 month sentence, he created a 39-panel mural illustrating heaven, hell and purgatory using contraband prison sheets, hair gel, plastic spoons, and newspaper clippings, that he smuggled out in the mail. Mr. Krimes jail-made art work and compelling story embody issues of prison reform, sentencing and social justice.

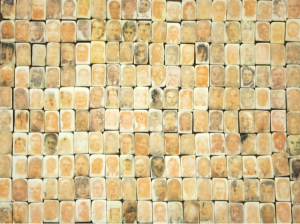

Arrested one month after graduating from art school in 2009 for possession of 147 grams of cocaine with the intent to distribute, the federal government increased the guideline range to 15-50 kilos on hearsay, as a prosecutorial tool to pressure him to cooperate or accept a plea deal. The sentencing guidelines increased from 30 months to a mandatory minimum of 10 years to life. As a non-violent offender in a lockdown violent offender unit awaiting sentencing, he wanted to occupy his time investing in something positive to transcend the tense environment and traumatic emotions that he says deteriorate your identity and self worth. Krimes read newspapers and magazines, in addition to philosophical texts on incarceration including Foucault’s “Discipline and Punish,” and Giorgio Agamben’s “The Kingdom and the Glory.” He was struck by the idea of using soap, issued by the prison to cleanse, as the perfect vehicle for his art, conveying concepts of purification, repentance and redemption -at least in theory-the ideal behind incarceration. Using the materials of the prison against itself, Krimes transferred faces from newspapers onto the soap, mostly mugshots of those who had just been arrested, looking directly into the camera, captured probably at the lowest point in their life, dehumanizing an individual at one point in time. The images leave a faint, ghostly inverse portrait when transferred onto soap, “a way to purify and inverse these other representations of these individuals in the media.”

Examples of “Purgatory”, 292 portraits of offenders created on slivers of prison-issued bars of soap using transfer from newspapers while in a 23 hour maximum security lock down for one year awaiting sentencing. Smuggled out in the mail, hidden inside used decks of playing cards.

Krimes signed an open plea agreement for 5-40 years and agreed to argue drug weights at sentencing, where the guideline range became 500g-2.5 kilos. Unwilling to cooperate and name his suppliers, he was sentenced to a 70-month federal prison term. The judge recommended a low security facility as close to his home in Lancaster Pa as possible, but instead the bureau of prisons sent him to Buttner NC, to the maximum-security ward of a medium security federal prison which, as he puts it, “houses every major organized crime syndicate and gang member from all over the world. Here Krimes spent his days drawing in his cell and soon other inmates came to ask him for portraits. Artists, he says, ”are the only individuals who can make something tangible to send to loved ones. But the artwork and the resulting conversations also humanized them to me and me to them.” After one more year, Krimes was transferred to an actual medium-security facility in Fairton, New Jersey. It was here that he worked twelve-hour days, seven days a week, for three years on Apokaluptein. Using prison bed sheets obtained from a friend in the laundry in exchange for stamps was a way to reveal the hidden process of production of UNICOR, which he describes as essentially inmate slave labor allowing federal prisons to earn enormous profits. Using images from newspapers and transferring them onto the sheets using hair gel to lift the ink and a plastic spoon to rub the image onto the sheet, he then drew and painted his own figures. They were smuggled out one by one in the mail. Krimes notes, “I never saw the entire piece together until I was released. I just kept the overall image in my head.”

After his release, Jesse was the lead plaintiff in a class action case against JP Morgan Chase, settled this past summer, that accused the banking giant of gouging former inmates with exorbitant fees on debit cards issued with their prison mugshots when they left prison. “Everything about the federal prison system is designed to grind you into hopelessness, coming home and trying to piece together a stable life, to have this very wealthy bank preying on you, was just unconscionable.” In his mind we are all offenders. No one is simply good, bad, right or wrong, it is much more complex. Today Jesse is an activist for prison reform and continues to create art on the themes of alienation and “otherness”, with an interest in systems and hierarchies, disentangling complex value systems and the human condition.

We very excited to welcome Jesse on February 23rd and to collaborate across disciplines with an exhibition at the Art and Art History Department, and co sponsored by the Office of the Provost and the Prisons and Justice Initiative.