One of the most common refrains in global health security is that pandemics don’t respect national borders. But the COVID-19 epidemic has turned up the heat under simmering disputes over Taiwan’s and Hong Kong’s status vis-à-vis the People’s Republic of China, reminding us that politics of sovereignty and autonomy don’t stop for pandemics, either. The virus might not care about borders, but the people confronting it certainly do. We saw this play out last week in the clash over Taiwan’s status at the World Health Organization (WHO) and the clash over border closures in Hong Kong.

Taiwan at the WHO

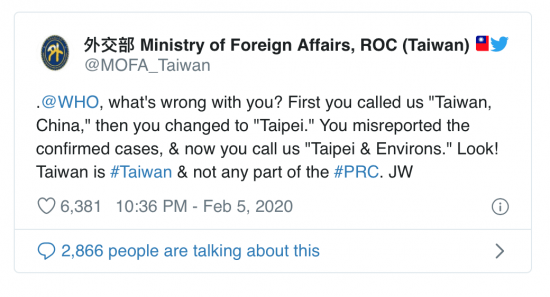

Because Taiwan is not a WHO Member State, the Secretariat can only interact with the Taiwanese government in limited ways, effectively subject to Beijing’s approval. Taiwan has protested that this endangers both the Taiwanese people and the rest of the world by limiting its ability to obtain information and participate in global response planning. (Also, Taiwan’s Foreign Minister is furious at WHO for referring to Taiwan as part of China, saying that this has caused airlines to cancel flights to Taiwan.) Several US Senators have taken up Taiwan’s case.

In response, Beijing insists that Taiwan is able to receive information from WHO, and has accused “‘Taiwan independence’ separatists” (i.e. the Taiwanese government) of “seiz[ing] on the opportunity to clamor for participation in WHO’s discussions, in an attempt to use the epidemic to expand the so-called ‘international space’ of Taiwan.” Viewed in context, protest over Taiwan’s exclusion from COVID-19 meetings are a spin-off of broader annual battle over whether Taiwan should be granted observer status at the World Health Assembly (which is itself part of a larger geopolitical gambit for gaining Taiwan greater international recognition). In practice, Taiwan’s standing within WHO depends on its relationship with Beijing. Under the previous administration, that relationship was warmer and so Taiwan was granted observer status from 2009-2016.

In short, both sides have a point. Taiwan’s exclusion does impede the public health response. At the same time, protests against Taiwan’s exclusions are politically-driven. As Alex Chiang, associate professor of international politics at National Chengchi University in Taipei, put it, “I think the WHO matter is more politics than real needs…Even though we are not in WHO, we can still get this info from many, many other places.’”

Meanwhile, the WHO Secretariat is, as ever, stuck between a rock and a hard place. A spokesperson reassured that “[i]n the event of an outbreak or health emergency, WHO works with Taiwanese health officials, as necessary, to facilitate an effective response.” But the example he cited is that Taiwanese scientists are included in all WHO’s expert consultations, which suggests that “work” is occurring via side-channels more than official channels. So while there is a clear public health benefit to Taiwan’s full participation in a coordinated COVID-19 response, that interest is, for now, taking a backseat to ongoing sovereignty disputes.

Border Closures in Hong Kong

Tensions over autonomy (if not outright sovereignty) are shaping Hong Kong’s COVID-19 response efforts as well. Since mid-2019, Hong Kong has been roiled by pro-democracy protests. Though COVID-19 has brought massive public gatherings to a halt, fear and animosity and towards Beijing are being channeled through the public health response. Carrie Lam’s administration has come under strong public pressure from across the political spectrum to close the border with the mainland. Last week, healthcare workers went on strike to demand just that. A poll from the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute showed that 80% of Hongkongers supported closing the borders and over 60% supported the strike—a pretty remarkable level of support in the midst of a public health emergency. The striking health workers argued that shutting down the borders was necessary “to cut off the source of the virus.” But the best scientific evidence shows that border closures don’t work, which is why WHO recommends against them. Rather, Hongkongers’ demands to close the border are grounded in hostility towards Bejing, anti-Chinese sentiment, concerns that keeping mainland border crossing open with harm Hong Kong’s economy, and residual trauma from SARS. In short, they reflect “the ‘cross-infection’ of politics in the current outbreak.”

Lam has implemented partial border closures, suspending rail travel (but not flights), shuttering all but three checkpoints, and instituting a quarantine for visitors from mainland. However, she said that “a full border closure is untenable.. because of the ‘almost unique’ situation between Hong Kong and mainland China.” The political reality is that Lam can’t close the border—not without approval from Beijing. Beijing has bent a little by agreeing to suspend issuing Hong Kong visas to travelers from mainland. (This number of mainland visitors has been a major source of tension since Beijing expanded the visa scheme, ironically, to help Hong Kong recover after SARS.) But for Hong Kong to seal itself off to protect against threats from the mainland would be a powerful reification of separation and autonomy. The symbolism is likely more than Beijing can abide or risk, especially coming after months of pro-democracy protests. (On the contrary, Xi is actively moving to tighten Beijing’s control over Hong Kong.)

The end result of this clash has been to undermine Hongkongers’ trust in their government at a moment when such trust is essential for an effective public health response to COVID-19. According to Ilaria Maria Sala, a Hong Kong-based journalist, “[t]he hostility towards both [the Hong Kong government and mainland China] has only been intensified by the epidemic.” The perception is that the government is unwilling/unable to protect the health and safety of Hongkongers, but only takes its marching orders from Beijing. Somewhat remarkably, Lam is now literally trying to reassure Hongkongers that her government is “‘not the enemies of the Hong Kong people’ and is working in their best interest.” Hongkongers are unconvinced. As Lee Siu Yau, a Hong Kong academic, explains, “our government’s lack of autonomy is no longer simply a political problem but now also a public health issue.”

As the COVID-19 epidemic unfolds, WHO Director-General Tedros has taken solidarity as his watchword, saying “[t]he rule of the game is solidarity, solidarity, solidarity” and “[coronavirus] is a test of political solidarity — whether the world can come together to fight a common enemy that does not respect borders.” For now, it appears that the pandemic threat is only intensifying sovereignty politics, not diminishing it.