The United States pays double for health care compared to other OECD countries and often has just as good, if not worse outcomes. These facts have become a consistent refrain for Democratic presidential candidates in a field defined by its different takes on Medicare for All. With millions of Americans still uninsured, the health care plans offered by many presidential candidates focus on expanding coverage—a process that will (unsurprisingly) raise total health care expenditure in the United States if current reimbursement rates are maintained. Though the number of insured Americans would change, the fundamental problem with health care in this country—we spend more than anyone without getting as much back—would not. It is increasingly important that the health care policy discussion thinks not just about how to expand coverage but also how to deliver care more cost-effectively without compromising outcomes.

At a fundamental level under our current fee-for-service system, health care expenditure can be reduced either by reducing prices or increasing the efficiency of utilization. That is a policy must either find a way to make providers charge less for their services or reduce the number of the services they provide without compromising patient outcomes. Almost all decreases in total health care expenditure from the most talked-about health reform proposals come from replacing private insurance reimbursement rates with often much lower Medicare reimbursement rates to providers. The allure of this method is pretty clear: use the negotiating power of the federal government to pay providers less than they currently receive while expanding coverage to millions of Americans. And the numbers seem to add up. The Mercatus Center found that projected health care expenditure would decrease under Sen. Sanders’ Medicare for All plan. The devil in the details, of course, is that it is unrealistic to expect a shift towards lower reimbursement rates free from disruption as many hospitals and other providers would face financial challenges.

A recent study by Song et al. reminds us that fee-for-service is not the only payment model we should be considering. In the study, researchers found that a two-sided risk global payment model used by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts yielded medical claims savings of up to 11% while maintain

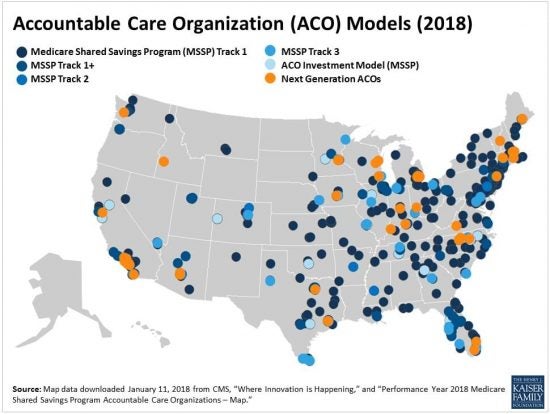

ing quality. A global payment model is the payment structure used by Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) whereby (as the paper describes) a provider assumes “responsibility for spending and quality, earning shared savings if spending is below the target, and…sharing financial risk if spending exceeds the target.” ACOs are not new to the American health care financing world. The ACA promoted the use of these systems to increase the efficiency of Medicare expenditure.

In other words, the (often public) payer agrees to a lump sum payment with a provider to cover the care of the insured population in the area. Providers receive bonuses for reaching quality and spending goals (usually through savings-sharing) and are penalized for inefficient or ineffective care. This payment system encourages providers to be efficient in their provision of services. While the successes of these efforts have been mixed, the Song et al. study should serve as a reminder that the health care policy debate should focus more attention on creative ways of sustainably reducing healthcare expenditure while maintaining and improving outcomes. ACOs and global payment systems are not the only alternative models to consider; a capitated system would provide many of the same benefits while more easily facilitating private payers. If presidential candidates want to bring bold new ideas to the forefront of policy attention, they would promote alternatives to the traditional fee-for-service model with plans that make health care not just universal but also universally efficient.

Photo courtesy the Kaiser Family Foundation