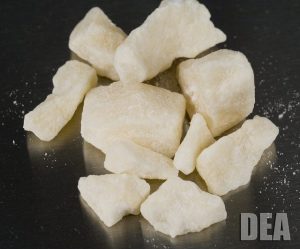

Crack Cocaine (Photo Credit: www.dea.gov)

I grew up in Brooklyn, New York in the 1980s. I saw a lot of things many children not raised in a big city never experience. One of the things I remember is seeing some of my neighbors – who had previously been vibrant people who chatted with my parents in the building lobby or waved to me while I stood at the school bus stop – become shells of their former selves caused by, according to my 10-year old comprehension, some mysterious illness. I would overhear my parents talking about them, but they were skillful to not reveal details in front of me and my sister. One night, one of my neighbors rang our doorbell. My parents were busy, so I answered the door as I often did. In front of me was my friend’s uncle. He was one of those “cool uncles” who would crack jokes with us, smoked cigarettes, wore a leather jacket (again, it was the 80s), and would sometimes hook us up with money for the ice cream truck . However, that night he appeared sweaty and anxious with bloodshot eyes. “Hey, where’s your mom?” he asked. All of a sudden, my father appeared and practically knocked me to the ground away from the door.

– “Hey, Mr. B, can I get a few dollars?”

– “No. You have to go. Do not come by this house anymore asking for money!”

– “OK. I’m sorry. I’m sorry.”

As I stood there confused with a look on my face to match, my father realized he had to tell me the truth about what was going on with the “illness” that had befallen some of our neighbors.

That illness was crack addiction.

I had heard about crack through rumblings at school or the occasional blurb on TV, but I didn’t think it was something that would ever affect me. That experience and my dad’s subsequent lecture on the emerging epidemic marked the chillingly harsh and permanent removal of the rose-colored glasses of my childhood. All at once my friends and I were aware of the empty plastic vials in the cracks of the sidewalks that we previously dismissed as innocuous litter. I watched those formerly chatty neighbors from my bedroom window as they stumbled out of our building late at night, looking more frail and twitchy each time, until I stopped seeing some of them altogether.

The National Response to the Crack Epidemic of the 1980s

“Crack” is a form of cocaine that is processed with baking soda to form small crystalline clumps (‘crack rocks’) that users smoke in glass pipes and ‘crackles’ as it burns, hence its name. Crack produces an instantaneous, brief euphoric high for its users, followed by depression, anxiety, exhaustion and ultimately brain damage. Traditional powder cocaine was expensive and was a drug of choice for wealthier people, but this process of cutting cocaine brought down the price to about $5-$20 per dose, making the drug accessible to low-income people.

The allure of crack spread swiftly through low-income, inner-city, mostly black and hispanic communities throughout the U.S. in the 1980s. As someone who is hispanic and was living in a mostly black and hispanic inner-city community in the 1980s and 1990s, I was quite aware of the impact of crack on my community. The terms “junkie”, “crackhead”, and “addict” became prevalent in the common lexicon and on the news. We school children were subjected to regular D.A.R.E. workshops where cops attempted to inure us with enough fear that we’d steer clear of drugs.

The most prominent reaction to this burgeoning catastrophe was the rise of the “War on Drugs” laws and policies enacted by federal and state governments. While First Lady Nancy Reagan was going around the nation telling children to “Just Say No!” to drugs, President Reagan was resurrecting the Nixon-era “War on Drugs” initiative by allocating $1.7 billion towards anti-drug law enforcement programs, which included changing laws to enable more charges and harsher penalties for drug-related crimes, and imposing mandatory-minimum prison sentences for drug offenses. The focus of the “War on Drugs” was, to paraphrase President Nixon, to treat drug abuse as “Public Enemy Number One” in the U.S. This policy emphasized criminalizing the manufacture and trafficking as well as the use of illegal drugs. Addicted persons were seen as criminals with anti-social behaviors rather than people with physical, mental or behavior health issues.

Throughout this peak in the epidemic, families were being devastated by heads of households becoming “crackheads”. Babies were born with debilitating drug addictions. The nation’s prison population exploded, with the number of people incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses jumping from 50,000 in 1980 to 400,000 by 1997. Federal laws were passed that imposed a 100 to 1 ratio on cocaine versus crack offenses, in an effort to deter growing crack usage. This meant that if a person in possession of 500 grams of cocaine got 5 years in prison, a person in possession of just 5 grams of crack cocaine would incur the same sentence. Since approximately 80% of crack users were African American, poor black communities bore the brunt of the criminal and societal consequences of the epidemic.

Using the “Disease Model” to address the Nation’s current opioid epidemic

Fast forward to current times when the nation is faced with another devastating drug abuse crisis. As it was to the crack epidemic, the government’s reaction to the opioid epidemic has been swift and aggressive, but it has had a noticeably less accusatory and punitive tone. There have been careful actions taken to minimize the use of stigmatizing words like “addicts” and “drug abusers”, instead referring to people as “persons who inject drugs” or “opioid misusers.” Instead of a crime and punishment “Public Enemy Number One” crisis, the opioid epidemic is being treated as a public health emergency, and those affected by it are seen as needing treatment and psycho-social interventions to remediate their problem. News stories that cover the epidemic foster sympathy for the people, families, and communities affected by this crisis, which are predominantly white, rural or suburban areas.

Rather than imposing mandatory harsh jail sentences for opioid offenses, courts are “sentencing” users to mandatory rehab. Fifty-nine million dollars in grants being issued by the Justice Department are not focusing on convicting and jailing opioid misusers, but rather providing resources to communities to improve their capacity to provide medical and behavioral health support to users.

What has spurred this shift in approaches? “Lessons learned” or demographic differences?

I cannot help but to look at the differences in approaches to these 2 drug crises with a cynical eye. There have been acknowledgements from government officials that the current holistic approach to the opioid epidemic was developed from the lessons learned from the harsh response to crack in the 1980s, but I would be remiss if I did not use my mantle as a public health and legal professional to not bring attention to the demographic differences of these 2 epidemics and how that may have influenced the government’s tactical approaches. The fact is that minority groups in the US are woefully accustomed to seeing this type of dichotomy when it comes to issues that affect brown Americans versus white Americans. Like it or not, that is still the reality of this country, even in 2017. Look at the relief response to Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. While there are always those who will scoff at the use of race to criticize governmental actions, those of us who have had to live and breathe racial and ethnic disparity our entire lives have become adept to reading between the lines and interpreting the subtleties of implicit bias in ways that those not from a historically discriminated-against racial group could never understand and quite frankly should not interject an opinion.

Overall, I am glad that the US is using a more holistic, treatment-based approach to the opioid epidemic, because it is proving to be catastrophic. However, I am saddened that millions of others were not given the same benefit to be saved from the grips of crack cocaine, and for their families to garner the same sympathy and compassion from the general public. Our jails are still filled with people serving obscenely long federal prison sentences for non-violent drug crimes. I also see little in the current opioid policies that benefit those affected by other drug epidemics like crack as part of an effort to make these holistic interventions available to them as well, to right the wrongs of the 1980s “War on Drugs” approach.

The nation’s response to the opioid epidemic should serve to reform its policies on drug abuse as a whole, not just drug abuse issues that affect certain populations.