Treatment courts (also known as drug courts), provide alternatives to incarceration and access to treatment for justice-involved individuals with substance use disorders. The more than 3,000 treatment courts across the country reflect their local communities, communities that too often lack evidence-based treatment for people with all forms of substance use disorder, including opioid use disorder (OUD). As the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine stated in its consensus report released in 2019, the vast majority of people in this country with opioid use disorder do not receive medication based treatment, the standard of care for opioid use disorder.

The three FDA-approved medications to treat opioid use disorder (M-OUD) are methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. M-OUD have been shown to reduce risk of opioid-related overdose death, OUD-related HIV and hepatitis C (HCV) acquisition and transmission, and recidivism. However, a 2013 study revealed that only 56% of treatment courts used M-OUD (methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone), despite 98% of these courts reporting participants with opioid use disorder (OUD).

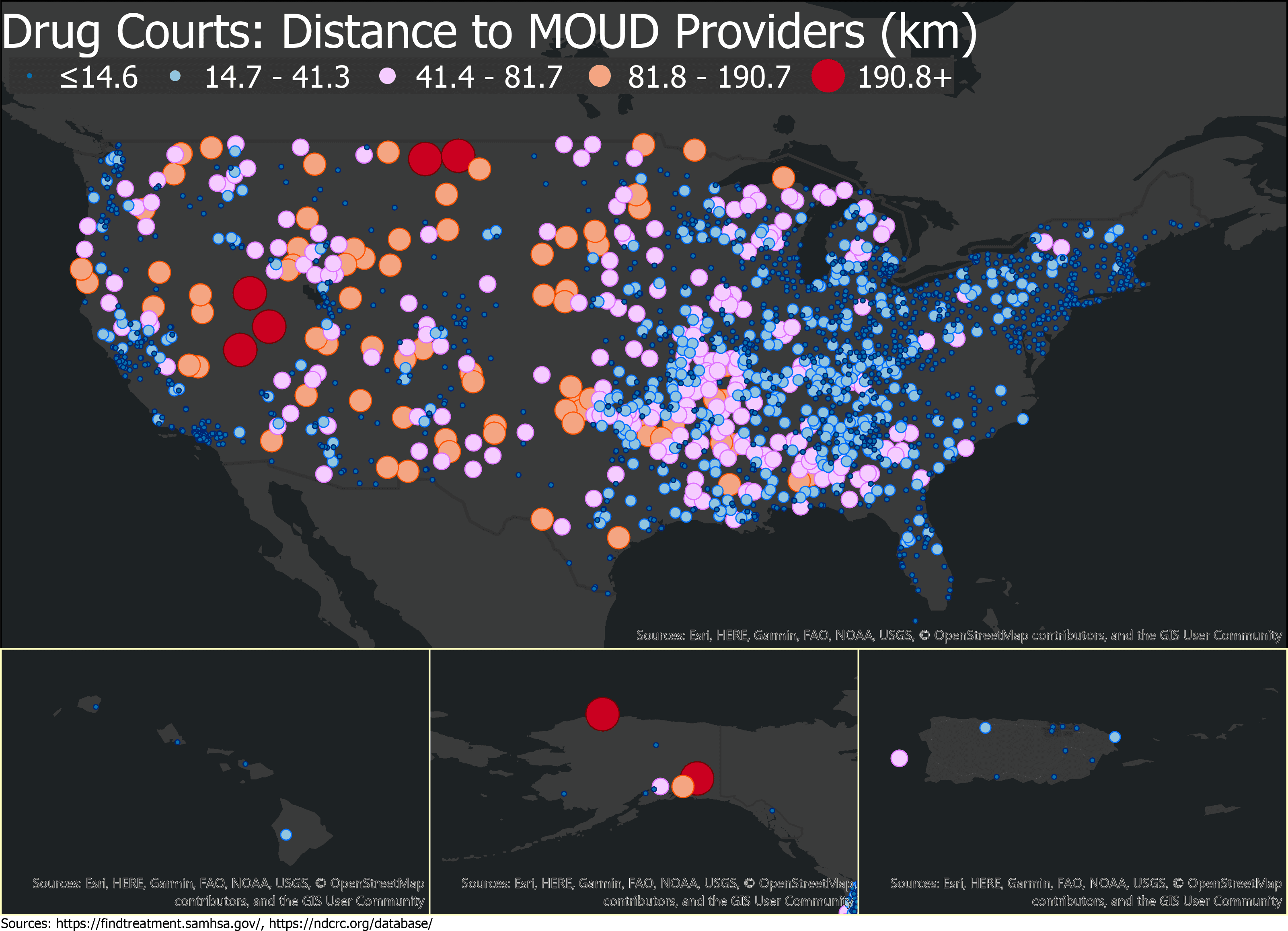

Even when M-OUD is offered, treatment sites are a great distance from the court, posing a significant barrier for court participants to consistently access treatment, both while participating in drug courts and after graduating from the program. This lack of community-based access is particularly pronounced in rural parts of the country; where over seventy-percent of rural counties lack a medication based treatment provider. These access challenges are counterproductive to the intended benefit of treatment courts to facilitate treatment and recovery for OUD and improve participants’ integration back into their families and communities.

The O’Neill Institute’s Addiction and Public Policy Initiative developed this interactive map of drug court proximity to M-OUD treatment facilities with the American Institutes for Research (AIR). This map illustrates the problem of community-based access to medication based treatment. For example, Nevada, which has rates of drug-related deaths, HIV, and HCV higher than the national averages, also has the greatest number of counties located 120 – 150 miles from one of the M-OUD treatment facilities in the state’s 3 major cities of Reno, Carson City, and Las Vegas.

The alarming rates of overdose deaths and new infectious disease cases resulting from the current opioid epidemic, and the evidence that people with OUD experience significantly better outcomes with M-OUD treatment make it clear that expanding access to M-OUD through treatment courts can play a pivotal role in improving the quality of life for people with OUD. The federal government has taken action to incentivize inclusion of M-OUD by requiring all treatment courts that receive federal grant funds to permit M-OUD. However, no one aspect of the system can provide the sole answer to bringing down rates of opioid involved morbidity and mortality. The answer to advancing evidence-based treatment must be system-wide, and comprehensive, strategies include increasing the number of trained M-OUD providers in both urban and rural communities, providing transportation options to treatment centers, and dispelling stigma and misunderstanding about substance use and M-OUD that cause communities to oppose medication based treatment facilities.

More information on best practices for drug courts and expanding access to medication-based treatment can be found in the O’Neill Institute’s Report, Applying the Evidence.