It was a subtle shift. In January, in a special session on Ebola, the World Health Organization’s Executive Board called for WHO’s Director-General to provide options for a contingency fund in the context of WHO’s “need for adequate resources for [its] preparedness, surveillance and response work.” For a moment, it seemed that any additional resources that WHO mobilized for the fund would be directed in part to epidemic preparedness, perhaps to build WHO’s capacities to prevent an outbreak from ever needing a major global response in the first place.

It was not to be. The decision at last month’s World Health Assembly was, as the term “contingency fund” implies, that the fund would be used to “scale up WHO’s initial response to outbreaks and emergencies with health consequences.” Response only, not preparedness.

This is part and parcel to a larger question. Is the global health community focusing too narrowly on responding quickly to an outbreak that has already occurred and reached some level of international concern, without due attention to preventing an outbreak in the first place, or stopping one at its very earliest phases? And are we focused too much on certain discrete – though vitally important – elements of the response – an emergency fund, an emergency workforce – while neglecting longer-term measures to prevent and minimize outbreaks (as well as broader WHO reforms)?

This focus on emergency response should hardly come as a surprise. It is endemic. We see it in the traditional emphasis on cure over prevention in the medical field. We see it in how the global community mobilizes for humanitarian emergencies in ways that we don’t for peace building (such as by supporting local civil society and peace-builders working to create more inclusive, harmonious societies) or development (such as developing safe housing to minimize the toll of earthquakes). We saw in with Ebola and the global effort, though belated, to stop the West African outbreak after having failed to take the measures – from an empowered and effective World Health Organization to investments in strong public health systems – that might have rapidly contained it in the first place.

The International Health Regulations (2005), a global treaty designed to prevent and control the international spread of disease, themselves suffer similarly. Developed through WHO, the IHR have 196 state parties. They require all countries to develop certain “core capacities” for disease surveillance and response (as well as border control measures). For example, countries should be able to rapidly detect unusual disease patterns that could signal an outbreak, take preliminary and additional control measures, and quickly communicate unusual events, and should have specialized staff, laboratory, and logistic capacities.

But what has been needn’t be what will be. With global health security high on the agenda, an appetite for reform, and a host of committees reviewing why the Ebola epidemic reached the heights that it did, this is an opportunity to give prevention its due.

There are some encouraging signs. The Obama Administration’s Global Health Security Agenda, launched last February, has three overarching goals, including prevention – along with detection and response – which encompasses the scope of threats: zoonotic diseases (like Ebola), antimicrobial resistance, and biosafety and biosecurity, while also covering immunizations. More recently, the Administration issued a National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria, with clear targets to reduce the incidence of deadly antibiotic-resistant bacteria, improve surveillance, and develop new diagnostics, vaccines, and therapies. The Administration is seeking $1.2 billion to combat and prevent the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, nearly double current levels. Meanwhile, WHO’s World Health Assembly passed a global action plan on antimicrobial resistance last month. A new Pandemic Emergency Facility being spearheaded by the World Bank is expected to be designed to incentivize countries to implement the core capacities of the IHR – at least a nod towards prevention – though the funding itself will be limited to emergency response.

More still is needed. Ebola reminded us of the vital importance of health systems more generally – the health workers, health facilities, medicines and other supplies, equipment, and information and other systems that ensure health care, or fail to do so. We need additional resources for and commitment to strengthening health systems, perhaps a new fund, and with immense potential, a Framework Convention on Global Health (FCGH) that would set standards, establish a financing framework, and in strengthen health accountability, building a critical element that was missing during the Ebola outbreak: trust.

I hesitate to say we should take prevention as seriously as the response when WHO’s emergency contingency fund will rely on voluntary contributions and the emergency public health workforce WHO oversees has no new dedicated funding, but at least the strategy is there. We need a similar global plan of action on epidemic prevention. Adopting the FCGH and increasing health systems funding, through a separate fund or other means, would be part of that agenda. Other pieces would build on the actions in the Global Health Security Agenda.

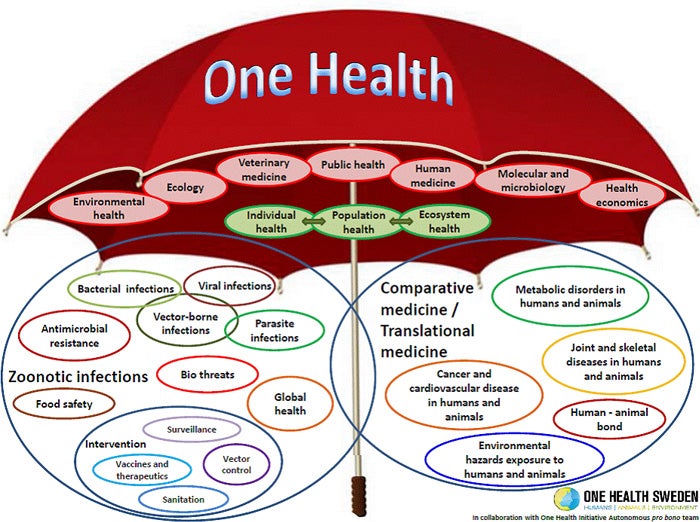

For example, this prevention agenda would significantly increase resources to carry out the One Health approach, which is based on the connections between human health, animal health, and ecology. This could include more research and action on the human-animal pathogen nexus. This would enable us to accelerate towards a more comprehensive understanding of what unknown or little known diseases might be lurking in animals — as well as better known ones like Ebola — and that might someday infect us. It would build research capacity around the world to conduct this research. It would enable real-time surveillance to detect and understand outbreaks and changing patterns of infectious diseases in animals. It would help us understand exactly how and where human activities are affecting the risk of transmission, and to take measures to reduce these risks. Epidemiologists, veterinarians, anthropologists, zoologists, virologists, infectious disease researchers, geneticists all have a role in this venture.

We should harness the information from these activities and increase resources for developing vaccines and therapies for emerging disease. And WHO should spearhead developing a global framework to equitably distribute these medical tools, so that if there is an outbreak, scarce vaccines and medicines go first to individuals and countries that most need them, rather than to those that can most afford them. We should accelerate research on the so-called universal influenza vaccine that, by targeting a stable part of the virus, could be effective against novel strains.

Along with One Health and health systems, we would invest more in social measures. As would come in part from community health workforces that the FCGH would support, building trust in health systems and health workers, is critical. What sort of “social vaccination” might be possible? These could be communication and education measures that anthropologists, communications experts, community leaders, educators, and health workers might design so that communities understand nature and threats of infectious diseases and – though the specifics will vary – the types of measures people might need to take, disruptions to their ordinary habits, to protect themselves, their families, and their communities. Are there ways to develop culturally sensitive responses before outbreaks occur?

One could even imagine reforms of the IHR themselves, unlikely though this might be. The IHR could be amended to expand their required core capacities to the types of actions in the prevention component of the Global Health Security Agenda. These could include actions linked to WHO’s global action plan on antimicrobial resistance and include, for instance, passing and enforcing laws on severely curtailing the use of antibiotics in animals, educating the public and health workers on the proper use of antibiotics, and to monitoring their use. Core prevention capacities could include establishing research programs and surveillance systems for zoonotic diseases and regulations to minimize the risk of their spread to people. And in a show of both global solidarity and enlightened self-interest, the IHR should incorporate a clear financing framework, including responsibility for wealthier countries to provide any necessary assistance to help fund these measures.

Given the challenge it would be to amend the IHR, more realistically, a global conference on global health security could convene to devise an action plan, with committed resources, to enable all countries to achieve not only current IHR-required core capacities, but also the types of capacities described above.

WHO reforms have focused on several discrete measures to enhance global health security, like the contingency fund and global health emergency workforce – and, critically for prevention, antibiotic resistance. These are necessary. But let us expand our focus to a still greater expanse of measures, such as those above and doubtless more, that will minimize the risk of disease outbreaks in the first place, and help ensure that we have the countermeasures – from the biological and medical to the community and social – at the ready.

Latest

Mantener la prohibición de la exhibición indirecta de productos de tabaco salva vidas

Ariadna Tovar Ramírez Fernanda Rodríguez-Pliego