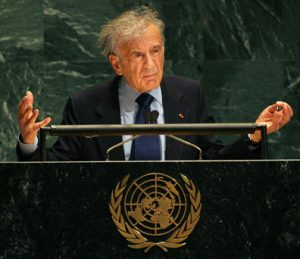

Elie Wiesel speaks at a UN General Assembly special session in 2005 commemorating the Holocaust. © Jeff Zelevansky/Reuters/Corbis

Indifference. In a word, that was the enduring evil against which Elie Wiesel – the Nobel Peace Laureate and Auschwitz survivor who died earlier this month – struggled, indifference to avoidable anguish. In a 1999 White House address raising the perils of indifference, Elie Wiesel offered these reflections:

Of course, indifference can be tempting – more than that, seductive. It is so much easier to look away from victims. It is so much easier to avoid such rude interruptions to our work, our dreams, our hopes. It is, after all, awkward, troublesome, to be involved in another person’s pain and despair. Yet, for the person who is indifferent, his or her neighbor are of no consequence. And, therefore, their lives are meaningless. Their hidden or even visible anguish is of no interest. Indifference reduces the Other to an abstraction….

[I]ndifference is always the friend of the enemy, for it benefits the aggressor – never his victim, whose pain is magnified when he or she feels forgotten. The political prisoner in his cell, the hungry children, the homeless refugees – not to respond to their plight, not to relieve their solitude by offering them a spark of hope is to exile them from human memory. And in denying their humanity, we betray our own.

The depth of the harm of indifference comes from how easy, and thus how pervasive, it is. I expect that is why other great advocates for human rights have emphasized the danger of indifference. In a 1965 speech, Martin Luther King, Jr., called “the greatest tragedy of this period…not the vitriolic words and other violent actions of the bad people but the appalling silence and indifference of the good people.”

Perhaps the greatest cause of indifference in today’s world, the normalization of terror – whether the terror of another terrorist attack, another mass casualty bombing, or the terror of a mother and her family as she hemorrhages uncontrollably after childbirth, soon to become one of a quarter million-plus women who die from pregnancy- or childbirth-related complications every year, with almost all such deaths preventable.

We read on the front pages of our newspapers about the world’s indifference to ISIS attacks in Baghdad that slaughter hundreds of people. Gun violence, with more than 30,000 Americans per year lost to gun homicide and suicide, fails to stir Congress to act. The normalization of suffering means that inequities can continue to be responsible for more than one in three deaths globally without producing global outrage, despite the monstrous toll of the epidemic of health inequity – 17-20 million people per year.

The normalization of terror, the seductiveness of indifference, and the ever-present need to struggle against it demands that we constantly, actively rouse our consciousness. And so Rep. John Lewis and his colleagues took the dramatic step of holding a sit-in on the floor of the House of Representatives to try to force a vote on meaningful legislation to address gun violence. In a memorable 2005 editorial, the New York Times reported, “Yesterday, more than 20,000 people perished of extreme poverty.”

Indifference is both individual and societal. It is being transfixed by last November’s terrorist attacks in Paris while moving on after reading a headline last week about an even deadlier marketplace attack in Baghdad. It is knowing that thousands of people die every day of easily avoidable causes, but living your life as though oblivious to that reality, except perhaps an occasional gift to charity. It is walking past a homeless person asking for help without even acknowledging her presence.

It is also systematically underfunding health systems – and foreign assistance – such that there is no doubt there will be too few health workers, too few medicines, too few ambulances, too little accountability to significantly cut the toll of mothers dying and robustly respond to the innumerable other causes of death and disability. It is allowing millions of children and adults with mental and physical disabilities to languish in mental institutions around the world, hidden away and forgotten, dying prematurely and living directionless lives, when love, attention, and proper care could transform and extend their lives, infuse them with purpose, and enable people with disabilities to be full members of society. It is giving little thought to prisoners who languish in squalid, abusive, inhumane conditions because they broke the law (or did they?), because they are criminals (and what combination of poor education, abuse, violent neighborhoods, economic hardships, contributed to their plight?).

Banishing indifference requires, I believe, recognizing that beyond being “troublesome…to be involved in another person’s pain and despair,” it is also beyond our capacity to give all the world’s ills, all people who suffer avoidable pain and despair, due attention. There is altogether too much of it. If we acknowledged each of those mothers, each of those victims of terror, of guns, each of these victims of indifference, we would have no emotional energy or time left for anything else, and still our task would be very much incomplete.

So at an individual level, we cannot do it all, though most of us could do more. I know that I could. To honor the humanity of others and of ourselves, to let the victim know that she is not forgotten, we could each develop our own plan of action against our own indifference. We may not be able to acknowledge every homeless person, but we can acknowledge that homeless person whom we pass by on the sidewalk, at the very least giving a nod, a recognition of their existence and humanity, and if possible, do more. If we find a way to show solidarity with the people of Paris after more than 130 people are killed there, we could take similar action after Baghdad’s marketplace attack. We can be more conscious of the how the food we eat, clothes we wear, and electronics we purchase are produced. We could take a little time out of each day to do something about unconscionable national and global health inequities, writing, emailing, calling our presidents and prime ministers, national and local legislators, about the need to create health systems that serve everyone equally, to address homelessness, to establish and fund policies that enable people with disabilities to reach their full potential, and so forth.

Collectively, if we each took such actions, even if we did not ourselves address every wrong, and every person wronged, every case of indifference – for this we cannot do – none of those wrongs will go without attention. None of the people who now suffer in silence will be forgotten, will have their humanity effectively dismissed by the rest of us.

Yet while acknowledging the humanity of people who are homeless is important, that will not in itself secure them roofs over their head. Giving the dead in Baghdad as well as Brussels, Pakistan as well as Paris, our respect will not end the bombings and other attacks. Our purchasing decisions will not in themselves change how corporations produce their products. Our emails and calls will make a difference only if our elected officials respond.

The ultimate answer to indifference is at the societal, structural level. And that answer, I believe, is human rights. If we structure our society around these rights, then we can truly be a society where indifference no longer reigns, where we do not with our silence tell millions of people – by failing to speak to their needs, their lives, their pain – that they do not matter, that their humanity is not really of concern to us. If we spend the maximum of available resources towards fulfilling people’s human rights, if we infuse equity throughout our policies, if we ensure people the opportunity to be part of the processes of crafting the policies that will affect their lives, if we ensure that none of our policies undercut people’s rights, if we provide avenues to people to challenge policies that people believe are tilted towards indifference to their plight rather than an abiding concern for their humanity – if we do all this, then we will be beginning a grand new chapter in the book of humanity.

Yes, there will still be questions. What is the best way to stop the carnage in Syria? How to raise sufficient resources and divvy up spending between health care, education, social safety net programs, equal access to justice….? How to balance the desire to save as many lives as possible with the fact that the lives of some of the most marginalized and underserved people in terms of access to health care, because of their remote location, may cost more money to save?

Even under a human rights approach, our solutions will be imperfect, and difficult questions such as these will persist. But in at least posing, struggling with these questions, we will no longer be a society of indifference. We will not be hiding from suffering, but confronting it. Elie Wiesel called love the opposite of indifference. A society that grounds its actions in human rights will be a society of love. It is for us to build.