Do the courts, and does the law more generally, have the power to advance the right to health? It would be hard to conclude at the end the O’Neill Institute’s weeklong Health Rights Litigation Intensive anything other than an emphatic yes — even while acknowledging limitations of health rights litigation, and exploring questions that make it difficult sometimes to even answer the seemingly straightforward question of what effect health rights litigation is having on the right to health. While hardly invariably so, the law, including litigation, can be a powerful tool to advance health rights – particularly when it is able to shift power.

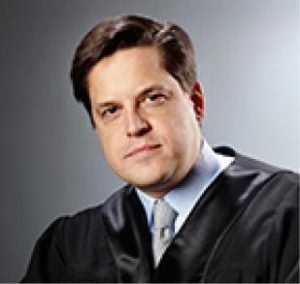

The health rights litigation intensive lived up to its alternative name of the Global School Health Rights Litigation Course, for it truly was a global school. The course featured a host of health rights experts, from as far away as Mexico – none other than Supreme Court Justice Alfredo Gutiérrez Ortiz Mena – to the O’Neill Institute’s own staff, along with top-notch professors, campaigners, and human rights funders. The course participants – many lawyers, but also students and other health rights advocates – came from countries spanning the global, from Uganda, Kenya, and South Africa, with a strong American contingency including from Mexico, Honduras, and the United States, as well as Asia, with South Korea well represented.

Mexican Supreme Court Justice Alfredo Gutiérrez Ortiz Mena. Image courtesy of the Supreme Court of Mexico.

This diversity matters, not only because the different perspectives enriched the experience for all, but also because, as came out from the various sessions, the experience of and possibilities for health rights litigation vary by country. And as histories of the court system and health rights litigation in India, Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, South Africa, and Mexico, demonstrated, the health rights jurisprudence of each court system and the very nature of that system are products of both judicial and political history, and the functioning of government institutions. Many of the courts most active in advancing health rights are those in highly unequal societies – Colombia, India, and South Africa, for example – with both the inequality and the courts’ sense of obligation to intervene a product, at least in part, of political dysfunction.

Whether judicial or otherwise, action to advance the right to health is most effective when it changes power dynamics on behalf of people who are poor, marginalized, discriminated against, on the short end of health inequities. Courts may have a role in changing these dynamics, as courts are a countermajoritarian institution that can exercise their authority to protect people’s rights, as Justice Gutiérrez emphasized. The court can stand for a robust implementation of the principle of nondiscrimination, as the Supreme Court did in Mexico, declaring unconstitutional a law establishing an employment certificate program for people with autism, where they could receive a medical certificate affirming that they had certain skills, meant to protect them from discrimination at jobs requiring these skills. Not only did the law reinforce stereotypes, but as Justice Gutiérrez stated, people’s right to be free from discrimination does not depend on their receiving a medical certificate. Power had shifted to people with autism. In the 760/08 judgment in Colombia, not only did the Constitutional Court demand a wholesale reform of the health insurance system, creating a unified scheme where the level of covered health benefits no longer depended on whether a person could pay into the system, but it also established a deliberative process to plan for the unification, with all stakeholders participating, and transparent justification for decisions. This representing a significant, if limited, opening of the political process to people otherwise kept outside and in the dark.

Matthews Myers, President of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, highlighted how international law, catalyzing national legislation, has begun to shift power away from tobacco companies, with 1.01 trillion fewer cigarettes sold in 2016 compared to what trends would have projected a decade earlier. This change, which included an absolute decline in cigarettes sold, is directly traceable to strong national tobacco control laws following the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the 2003 treaty that came into force in 2005. Indeed, Bloomberg Philanthropies estimates that tobacco control laws that took effect in 2007 through 2015 will save 30 million lives. Yet even that shift is far from complete. Tobacco has been on track to kill 1 billion people in the 21st century; it will take bolder use of the law still, such as holding tobacco executives personally liable for the carnage their products cause, to fully turn the tide.

Another place where changing power dynamics matters: corporate codes and other initiatives aimed at upholding the rights of workers, protecting the environment, and benefiting communities. Chris Jochnick, formerly of Oxfam America, said that the value of these initiatives is all about power. Do they add to stakeholders’ power, or not? Only when there is a meaningful shift in power, such as by providing legal remedies for violations and increasing people’s access to information, can they make a difference.

The power of the law to advance the right to health does not mean, though, that understanding the effects of courts on the right, or the best way to implement it, are straightforward matters. After years of debate centered on Brazil and access to medicines, but looking beyond as well, questions remain about the degree to which right to health litigation has advanced this right, particularly the demand for equity and the emphasis on poor and marginalized populations that are at the right’s core. Not only are different lines of evidence open to different interpretations, with incomplete data further complicating the task, but we must recognize hugely important normative and counterfactual questions. Even if the very poorest are not the main beneficiaries in a particularly country, for example, is it enough if the poorest 40% of the population are? Would they be worse off absent judicialization of the right to health? Or, it may be that the court cases require the government to spend money on higher cost treatments that disproportionately benefit the better off, but would the government have otherwise spent the money on public health and other measures particularly important to poorer segments, or would it have put those funds to some other purpose, perhaps not related to health at all?

Difficult questions also arise in other contexts that came up during the course, such as abortion, featured during one session organized to highlight a new special Health and Human Rights Journal issue on human rights and abortion. For example, there can be a conflict between perspectives of women’s rights advocates, and the need to fully afford women their reproductive rights, and people with disabilities, concerned that abortions, particularly combined with genetic testing, will target future members of their communities. Another question involving people with disabilities that came up during the course: when should people with intellectual disabilities be able to adopt children? How to ensure both the rights of people with disabilities and the best interests of the child?

From searching questions to practical skills, with a moot court and fundraising pitch concluding the course, from lectures to discussions and interactive exercises, the health rights litigation course proved most rewarding for those able to attend. And above all, the passion of the attendees for their charge of health rights served as a reminder that the field’s future holds great promise. For all the power – if at times controversial or questionable, and yes, limited – of health rights litigation and the use of the law to advance people’s possibilities of realizing the right to health over the past several decades, the potential in the years ahead is greater still.