If you were in New York City and its environs in the weeks and months after September 11, 2001, as I was – or, I expect, just about anywhere in the United States – you will recall the American flags in the storefront windows, outside homes, everywhere really. Those banners of solidarity reminded us, as one song of the time had it, we were all Americans. It was a time of solidarity in our unity, in our oneness. It was time of our national motto, e pluribus unum – out of many, one – with an emphasis on the unum.

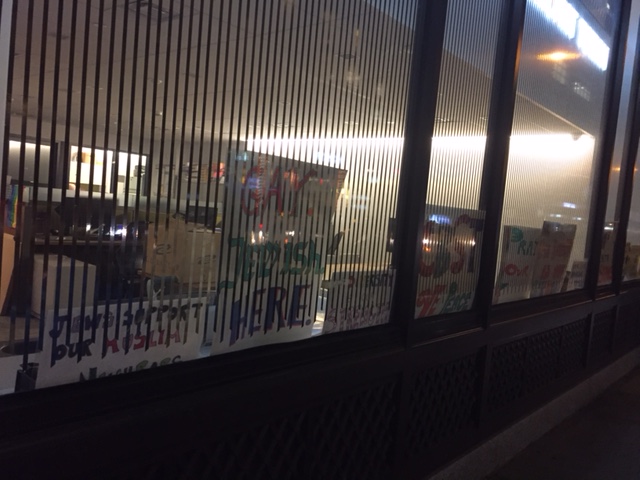

I was reminded of this not long ago when I saw another window display in New York, at a synagogue in midtown Manhattan. It spoke of another kind of solidarity. “Our Diversity Is Our Strength,” read one sign. “Gay and Jewish Here!” proclaimed another. “Jews Support Our Muslims Neighbors,” affirmed a third. This was solidarity for modern times: solidarity in our diversity.

This is the solidarity of peoples who will not be divided. It a type of solidarity the global health movement knows well. Think of “I am HIV positive” t-shirts, worn by people living with HIV/AIDS — and by people without HIV, standing in solidarity.

And it is the type of solidarity we need now, to counter policies and rhetoric in the United States that would divide us, and further marginalize the marginalized. And what a toll these policies are taking. Research a few years ago revealed that “in families with one or more undocumented parents, the threat of detention and deportation is harming the mental and physical health of their children.” These effects included being twice as likely as other children not to have access to medical care and high rates of symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder. How much worse all this must be now, with no undocumented immigrant feeling safe from the threat of deportation. Another study reported similar findings and others, such the high likelihood that children of an undocumented parent who has been deported or detained will have insufficient food. This second study also found that partners of undocumented immigrants who have been deported have a lower income that is associated with a shortened lifespan.

Immigrants with legal documents, particularly Latinos, in California and elsewhere are canceling or not applying for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program despite qualifying. They fear that legally present immigrants who access public assistance programs are next up for deportation, or that using public assistance programs will reduce their chances of becoming citizens. And they are reacting to the general atmosphere of fear from raids by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. Health consequences of food insecurity include “increased rates of depression, diabetes and other chronic illnesses, and mental and behavioral problems in children.”

Like the signs in the New York synagogue, there are things we can all do, from speaking out and political activism to visible displays of solidarity, like posting our own signs, or waving flags proclaiming our oneness (rainbow flags, flags celebrating our diversity [in Spanish]), or wearing t-shirts of solidarity (how about taking a page from the HIV movement: “I am an undocumented immigrant, and America is my home”), to take a few possibilities.

There are also things that those of us in the health sphere can do. Along with speaking out against policies that harm people’s health – a failing of the obligation to respect the right to health, among other rights – and always ourselves being respectful towards all people, we can promote health policies and tools that reflect unity in our diversity. National health equity strategies could lead to comprehensive strategies to advance health equity, addressing each marginalized population and covering not only the health sector, but also all other spheres of life that are part of the social determinants of health. Regular use of health impact assessments – even where now rarely used, such as for immigration policies – would at the least make transparent the health harms of divisive policies, and may go a step further in insisting on a different approach. Globally, a Framework Convention on Global Health could embed approaches such as these into international law, and help create the spaces where those who now face disparagement and discrimination can make their voices heard.

We are one, and we are many. That is our strength. If we let the tempest of our time toss aside some of us, we let today’s storm toss us all into the sea of inhumanity. And that is why, if we are to stand for humanity, we will stand for each other.