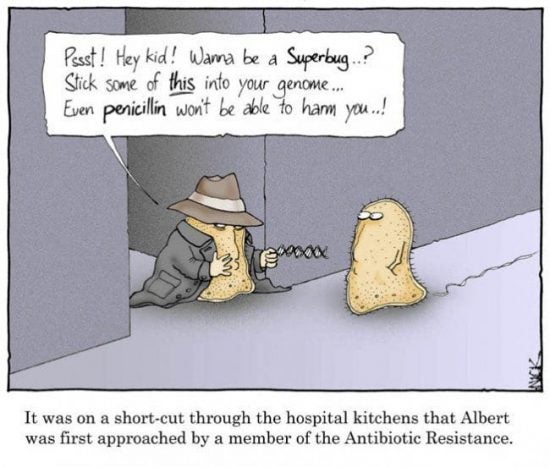

Image courtesy of i-sense.

If the story weren’t so important and playing out in real life every day, it would be a stale and tiresome story: the world’s leaders making transformative-sounding commitments, go back to their capitals, and continue mostly business as usual, perhaps with a new initiative here, modestly increased funding here.

In 2016, the world’s leaders committed to action at the UN High-Level Meeting on Antimicrobial Resistance, endorsing WHO’s Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance, issued a year earlier. Yet a development that emerged from a corporate front office, but should sound alarm bells far and wide on how far we are from the necessary action. One of the few remaining major pharmaceutical companies still in the business of developing new antibiotics, Novartis, announced earlier this month that it would end its antibiotic development program.

In a world of growing antibiotic resistance – causing some 700,000 deaths globally every year – we are in desperate need of new antibiotics. You may have heard of MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), one of the most prominent of the hospital-acquired antibiotic resistant infections, though may be less familiar with CRE (carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae), which former U.S. CDC Director Tom Friedan called “nightmare bacteria” and are resistant to a class of antibiotics often used as a last resort. The biggest burden, though – as ever – is in lower-resource countries, above all multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), killing about 240,000 people in 2016.

There are three pillars to combatting bacterial resistance and resistance of other microbes. (Together, resistance of all microbes is referred to antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotic resistance refers to drug resistance in bacteria, which is the greatest threat.) One, reducing unnecessary and inappropriate use in people; two, reducing unnecessary and inappropriate use in farm animals (including ending entirely use for growth promotion and prevention), and; three, research and development of new antimicrobial drugs and rapid diagnostics. All of this must be backed by thorough and careful surveillance.

A central reason for the lack of new antibiotics is the lack of economic incentives for drug companies to develop them. They are for acute rather than chronic illnesses, meaning patients will generally need them for only short periods of time, limiting sales. Meanwhile, with the urgency of conserving newer antibiotics to slow the development of resistance, stewardship demands that they are used only when truly necessary and older drugs are unlikely to work. And with the bulk of the disease burden in poorer countries, responsible companies will accept limited or no profits for a significant portion of potential sales. It is not a formula for blockbuster drugs.

That companies like Novartis are divesting from antibiotics does not entail a total loss. Novartis, for instance, plans to sell its current antimicrobial projects, while AstraZeneca, another pharmaceutical company that recently got out of the antibiotic business, sold its antibiotic division to the pharmaceutical giant Pfizer, which continues its antibiotic development work. Meanwhile, many smaller biotechs are researching new antibiotics, and new models of public-private cooperation, with a significant role for academics and “an open approach to development and discovery,” are emerging. Whether this can begin to make up for the exodus of most major pharmaceutical companies is an open question, though, and the stakes could hardly be higher.

There are no shortage of proposals incentivize research and development of new antibiotics and other antimicrobials. And between governments and WHO, several initiatives – a Global Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Research Innovation Fund aiming to secure £1 billion, the Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership, and the U.S. Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator – are underway. These are, however, even collectively, far from the scale proposed by the Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, a high-profile UK commission that issued its final report in 2016. Its proposals included $16 billion per decade to incentivize new antimicrobials, $1 billion per year to spur investment and development of new rapid diagnostics, and a Global Innovation Fund, with an initial $2 billion over five years. Meanwhile, the world is falling far short on funding R&D for tuberculosis, though new drugs and diagnostics are critical to reversing the spread of MDR-TB, with $9 billion required from 2016 through 2020.

Encouragingly, a Democrat and Republican in the House of Representatives teamed up to introduce the Re-Valuing Anti-Microbial Products (REVAMP) Act of 2018 in the end of June. The legislation empowers the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to award developers of new antimicrobials that have been designated as priorities an additional 12 months of market exclusivity for the drug of their choosing – and not that antibiotic, which requires careful stewardship. Developers may also sell this right to market exclusivity, which could be worth a billion dollars or more. The legislation authorizes ten such awards.

The most hope comes from scientists. From the gene-editing tool CRISPER to massive computing power, from nanoparticles to the Komodo dragon, from synthetic biology to the innovative iChip device used to discover antibiotics in soil-dwelling bacteria, they have developed powerful new tools for drug discovery, and have wasted no time in putting them to good use. Just this year, scientists discovered two new classes of antibiotics. (Each class of antibiotics shares similar chemical properties and mechanisms of action.) Scientists at Brown University and several other universities and hospitals in the region screened 82,000 synthetic compounds, identifying compounds that could be used to fight MRSA. And researchers from the University of Illinois and a French biotech startup, Nosopharm, discovered naturally occurring antibiotics in the soil-dwelling nematode worms, leading to another new class of antibiotics. With only 22 classes of antibiotics currently on the market, this is no small accomplishment, though for both recent discoveries, there is a long and uncertain way yet from the laboratory to the doctor’s office.

The science marches along. But as long as the politics and the economics are out of step, including woefully inadequate public financing, that is not likely to be enough. It is bad enough that we increasingly see the term “superbug” – significantly unusually resistant pathogens – in our headlines. It will be worse, though, if the term falls out of fashion because such microbes are no longer exceptional, but have instead become the norm.