When we talk about how cultures need to change, we often think of someone else’s culture. Cultures in regions where women need permission to leave home, or where a husband beating his wife is an accepted practice, or where sexual minorities are shunned and subject to severe sanctions. We think of a country in Asia, Africa, or the Middle East.

All this is true. Practices such as these, even ones that may have may have existed for hundreds of years, are deeply at odds with human rights, with current values such as inclusion, with today’s world.

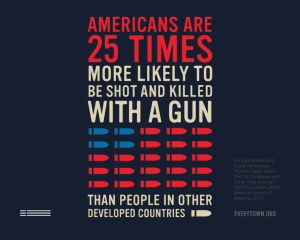

But we need some cultural changes here in the United States too, including in areas link to two of our country’s hot-button issues: gun violence and immigration.

Image courtesy of Everytown.

One of the arguments used against gun control, particularly regarding national action, is that guns are part of the culture in some of the country, particularly in the West, in the South, in rural America. The link between guns and that rugged American individualism, between guns for hunting – perhaps a father and son activity, or a group of friends joining together in camaraderie – these have deep roots.

But in today’s world, this culture can have deadly consequences. The evidence in plain that gun deaths are higher in states with looser gun regulations and with more guns. School shootings and other gun crimes can happen anywhere. People may attempt suicide anywhere. Wealthy countries that don’t have this culture – and have much tighter gun laws – have only fraction of the gun violence that the United States experiences.

In the area of immigration, the issue is not so much an ingrained part of the culture of America that needs to change, as much as it is accepting that the culture is already changing. One of the factors behind opposition to immigration among some white Americans is a sense that they no longer belong. As National Public Radio reporter Michele Noris reported from a town (Hazleton) in Pennsylvania, once 95% white and now more than 50% Latino:

Going to the doctor’s office and suddenly looking around and realizing that everybody else is Hispanic. Going to the local Walmart … and realizing that, “Boy, the things they’re selling in the produce aisle are different,” or “There’s a whole aisle where everything is in two languages, and I never noticed that before.” … “Suddenly it feels like this community that I knew so well” — so what they were saying is that they don’t feel like it’s “theirs” anymore. …

Image courtesy of CE Units.

Along similar lines, a poll of white working class Americans last year found that 49% of respondents agreed with the statement that “things have changed so much that I often feel like a stranger in my own country.”

Different languages, people who look different, different foods, perhaps people who pray differently – yes, our culture is changing. As we encourage people in deeply conservative regions of the world who see their cultures changing – women holding economic and political positions of power, perhaps, or practices like female genital mutilation and child marriage on their way out – to embrace these changes, so must we do in the United States.

The most effective changes are driven from within the community, not from people on the outside (like me). Rather, just as women’s groups and Muslim organizations are at the forefront of changes for women’s rights and tolerance within deeply conservative societies, the changes at home will be homegrown, from people who have an intimate understanding of the cultures that need to (or are) changing. People from areas where a culture of guns persists, communities with a changing complexion – they will be, and need to be, leaders in driving and accepting these changes.

Those of us on the outside are not powerless. Just as funding women’s NGOs in conservative societies can help enable their leadership to flourish, perhaps we – as individuals, as NGOs, as foundations – could support skills building for people in these communities and regions who want to act, but may need assistance with the skills to do so. Maybe funding from the outside, including from the federal government, could support English-language training for immigrants who so desire – which could both open up new economic opportunities for them and lessen the discomfort of their neighbors, easing the transition.

Accepting that your culture is changing, or demanding that it does change, may be a difficult and not immediate process. Those of us not part of these cultures should try to understand the difficulty of letting go of what you know.

And we should examine whether there are assumptions that we have about our own cultural environments that should change. Just as I am not from, for example, Afghanistan, I am not from the rural South. And while I grew up in a largely white, upper-middle-class New York suburb, and now I live in a mixed-income apartment building in Washington, DC, where my floor has a mix of individuals and families white and black, Arab and Latino – I am among the very many Americans who embrace these changes, who see in them our own values, so it is no burden to me.

Culture change is not easy. But cultural evolution is the way of the world, to conform to evolving values and realities. For the sake of our country, I hope that we can embrace the need for such an evolution here at home.